I had a wonderful few days in Reykjavik at the 31st Congress of Nordic Historians (NHM), perfectly organised by the University of Iceland. It was the first time I attended NHM and it was highly stimulating and inspiring to attend various talks and panels, especially on different topics than mine. It was also the occasion to meet old friends and colleagues and make new ones.

I had the distinct honor of presenting my work as part of the panel, “The history of knowledge: Empirical Approaches to the History of Knowledge,” organized by Evelina Kallträsk of Lund University. It was a true pleasure to participate along with Mikko Myllyntausta (University of Turku), who presented on microhistorical knowledge networks, and Victoria Van Orden Martínez (Linköping University), who discussed the circulation of women’s scientific knowledge under Nazi persecution. Although we had different cases from different periods and places, our studies provides a good picture of how our empirical work contributes to the history of knowledge.

My Contribution: Old Books, New Questions

My paper, “The History of Knowledge through Early Modern Private Libraries: Empirical Findings and the Digital Humanities,” delved into a set of core questions that drive my current research: What can private libraries really tell us about early modern knowledge? How can digital tools help us reconstruct the intellectual worlds of historical actors? And fundamentally, how can we better connect a collection of books with the mind of its owner?

My case study is the private library of Don Juan José de Austria (1629-1679), a significant political and military figure in 17th-century Spain. My primary source is a manuscript inventory of his collection, compiled just after his death in 1681. By transforming this static manuscript into a dynamic dataset, we can begin to see the library not just as a collection, but as a cognitive tool.

Uncovering the Findings: The Shape of a Mind

After transcribing the manuscript and collecting the data, the task is to identify the original edition of the books mentioned. The task is time-consuming because the book titles and the authors’ names are shortened and translated into Spanish. Some books are also manuscripts. The search for the right book through various combinations in online libraries such as the Universal Short Title Catalogue, the Spanish National Library, Google Books, or Gallica, could take me an entire work-day or even two. But then I tried a simple query in an AI assistant. I asked if it could fins this book: “Un tomo mano escripto de astrolauro por Miguel Coyneti”, as I was not even sure of the spelling.

After a few seconds, it came back with this answer: “likely refers to a manuscript on the astrolabe by the renowned Flemish mathematician and instrument maker, Michel Coignet.” And it showed the reasoning behind this, the links, and a few words about Michel Coignet and his work. In other words, it corrected the spelling for “astrolauvo”, with the “v” being pronounced “b” and written similarly as “u”, and it understood that “Miguel Coyneti” was a hispanisation of Michel Coignet, who was famous for his work on the astrolabe.

The initial findings, which I presented at the conference, are already painting a fascinating picture of how knowledge was organised and valued in this specific context.

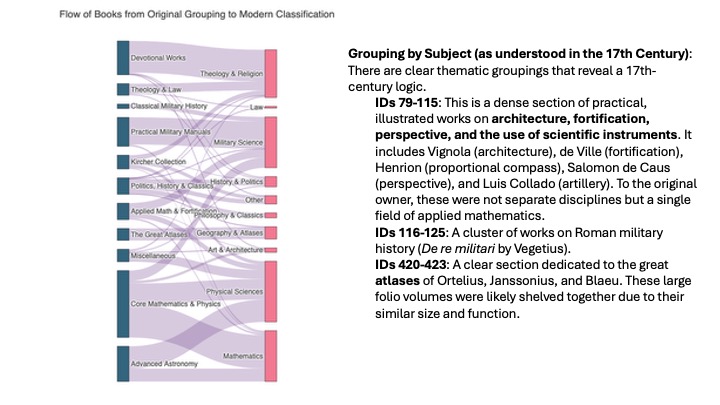

- The Logic of the Shelves: There was a very practical, “local” ordering of knowledge. Books on perspective and architecture were placed right next to texts on military fortification, suggesting they were seen as part of the same toolkit for engineering and warfare, rather than as separate artistic and military disciplines.

- A Prince’s Preoccupations: Unsurprisingly, the library is dominated by works on military science and mathematics. This confirms Don Juan José de Austria’s professional interests, but the dataset allows us to quantify this in new ways and see which specific sub-fields held the most weight.

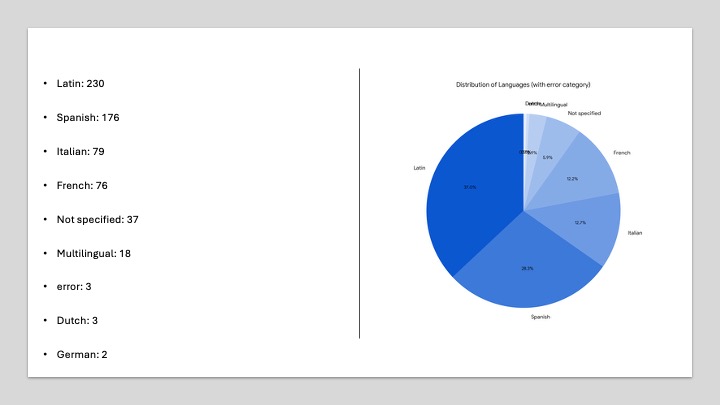

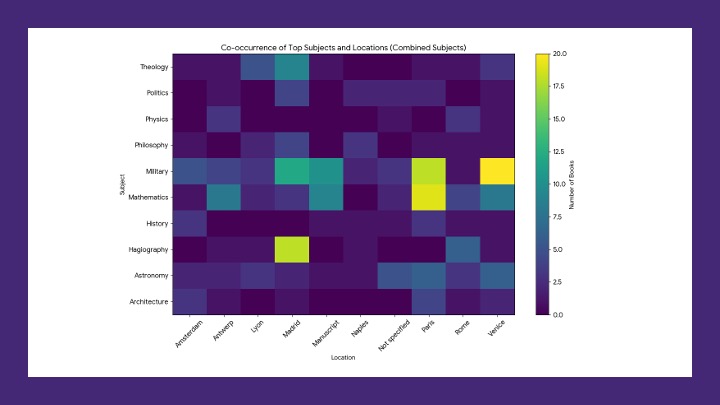

- Mapping a European Republic of Letters: The data reveals a clear linguistic and geographic logic. Latin was the language of choice for more abstract, academic works, while vernacular languages (Spanish, Italian, French) were used for practical, hands-on manuals. Furthermore, we can map the hubs of European printing for different subjects in this library: Paris was the centre for mathematics, Venice for military texts, and Madrid for hagiographies and religious works.

The Future is Now: AI, Handwritten Text, and New Challenges

This is only the beginning. The next phase of the project is to scan Don Juan José de Austria’s extensive correspondence and use Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) to create a searchable digital archive of his own words. By leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) and other AI-driven tools, we can then perform a large-scale analysis of his political thought and compare it directly with the intellectual resources we know he had on his shelves. The possibility of automating transcription, identifying original editions, and analyzing thematic patterns across thousands of pages is transformative.

But this exciting frontier also presents our field with profound challenges that we must address directly. In my talk, I concluded by posing two questions that I believe are crucial for all of us working in the humanities today:

- Ethics: What are the ethical considerations in training AI tools on historical data? How do we ensure transparency and account for the biases they inherit from their training—and from us?

- The Role of the Researcher: As more of our traditional tasks (transcription, source discovery, data analysis) are augmented or replaced by automation, how does our fundamental role as historians and interpreters of the past need to reconsidered and redefined?

The conversations that followed my talk, both in the Q&A and in the halls of the university, were incredibly rich. The path forward is one of collaboration, critical thinking, and a willingness to embrace new tools while holding fast to the core principles of historical inquiry.

This research was generously supported by a María Zambrano Grant for the Attraction of International Talents to Spain (funded by NextGenerationEU) at the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, where I am affiliated with the CINTER Research group of excellence in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities.

Leave a comment